The Visual Commentary on Scripture (VCS) is a freely accessible online publication that provides theological commentary on the Bible in dialogue with works of art.

Each section of the VCS is a virtual exhibition comprising a biblical passage, three high-resolution (zoomable) art works, a short commentary on each one, and a longer ‘comparative’ commentary drawing them together.

Using visual art to help unlock and support understanding for pupils

VCS exhibitions aim to transform interaction with Scripture. Our hope is that our users will never read the biblical passages or see the art works in the same way again.

The exhibition curators represent a diversity of disciplines, methodologies, and perspectives as they explore illuminating interactions between the text and images. Their choice of artworks ranges from the ancient world to the contemporary: you’ll find Hans Holbein next to Banksy, and video art alongside illuminated manuscripts.

Hermeneutical principles

The VCS is a constructive contribution to living traditions of thought and practice that converse with the Bible as an authoritative resource in contemporary contexts.

Its theological hermeneutics align with the seminal defences of the role of images in Christianity advanced by theologians like John of Damascus. Artworks are selected on grounds comparable to those that governed the choice of commentary for inclusion in Jewish Talmud or in Christian Catenae: not because they all said the same thing, but because their insight and dialogical potential were fruitful for their communities.

Interdisciplinary thinking

The VCS is a theologically driven project, informed by biblical studies and art history, with an interdisciplinary team based in the TRS department at King’s College London. Each page of the VCS is theologically ‘curated’, and each has the potential to become a dramatic event, perhaps even an ‘epiphany’ for the viewer.

The contemporary conversational engagement of art with Scripture builds mutual understanding and creative perspectives on present issues for non-religious as well as religious audiences, in our increasingly polarised times. Visual art offers an hospitable space for multiple viewpoints to be explored, and the ‘conversational’ mode of interaction fostered by groups of three artworks promotes peaceable rather than conflictual interpretative practices.

The VCS in the classroom

RE teachers are already discovering the VCS and using it in the classroom. You can search the website by book within the Old Testament and Apocrypha or New Testament or by theme (e.g. Wisdom, Creation, Miracles…), explore a ‘spotlight’ topic (currently Coptic and Ethiopic art), use the video channel, or learn more about the hermeneutical principles behind the VCS. There are 265 exhibitions currently online, and hundreds more in the pipeline.

The VCS is working on tailored school resources to bring the Bible alive in new ways for students. If you would like to join a focus group for school resources, or pilot them in your teaching, or if you’d just like to discuss ways of using the VCS, please contact Dr Chloë Reddaway at vcs@kcl.ac.uk

You can subscribe to the free VCS mailing list at the bottom of the homepage.

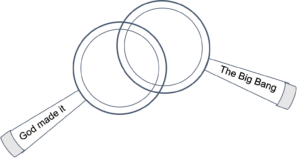

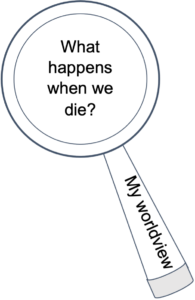

I have bought several magnifying glasses to add to the explanation. This has helped students to understand that we all have different personal worldviews as I hold them up when explaining each individual view. It also helps to illustrate other worldviews. I have also shown how these lenses can ‘cross over’ which illustrates how views can be ‘combined’. An example was when we were discussing ‘how did the world get here?’ Students came up with answers ‘God made it’ and ‘the Big Bang’. I held up a lens for each of these views and then crossed them over. For some students this was a new Christian worldview; that God created the Big Bang.

I have bought several magnifying glasses to add to the explanation. This has helped students to understand that we all have different personal worldviews as I hold them up when explaining each individual view. It also helps to illustrate other worldviews. I have also shown how these lenses can ‘cross over’ which illustrates how views can be ‘combined’. An example was when we were discussing ‘how did the world get here?’ Students came up with answers ‘God made it’ and ‘the Big Bang’. I held up a lens for each of these views and then crossed them over. For some students this was a new Christian worldview; that God created the Big Bang.