An investigation into Buddhist values through a study of the Buddha’s enlightenment and one of his previous lives.

KS1 and lower KS2. Originally written by Lorraine Haran, updated in April 2019.

Key Buddhist Teachings (background for teachers)

The Four Noble Truths

- Life involve suffering (dukkha).

- The origins of suffering lie in wanting, which is made more intense by greed, hatred and ignorance (Samudaya)

- The ending of suffering is possible (Nirhodha).

The Noble Eightfold Path is the way to end suffering and become enlightened (Magga).

- Right understanding (seeing the world as it is, in terms of the Four Noble Truths).

- Right Thought (commitment to follow the path).

- Right Speech (truthfulness, gentle and useful speech).

- Right Action (following the Five Precepts with love and compassion).

- Right Livelihood (avoiding work that causes harm or injustice, choosing one which is beneficial to others).

- Right Effort (avoiding bad thoughts, encouraging good).

- Right Mindfulness (attentiveness and awareness).

- Right Meditation (training the mind in meditation).

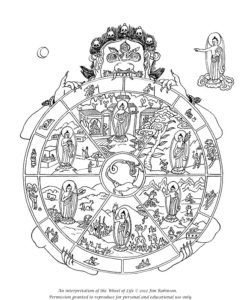

(When people follow the path, the wheel turns in a positive direction traditionally clockwise symbolising their development).

The Five Moral Precepts: Buddhists should refrain from:

- Harming and killing living beings,

- Sexual misconduct,

- Taking drugs or drinking that impair clarity of the mind,

- Taking what is not freely given,

- Wrong speech.

(There is a positive aspect of each precept, e.g. it is not enough not to harm – one should show compassion for all living things).

Enlightenment and Nirvana: Buddhist believe that there is a cycle of birth, life and death and rebirth. This goes on and on. They believe that unless someone gains Enlightenment, when they die they will be reborn. If a person can gain Enlightenment, they can break out of this Breaking out of the cycle is called Nirvana (sometimes called Nibbana) It is the end of everything that is not perfect. It is perfect peace, free of suffering.

Meditation: Buddhists try to reach Nirvana by following the Buddha’s teaching and by Meditation means training the mind to empty it all of thoughts. When this happens what is important comes clear.

Buddha: the ‘Awakened’ or ‘Enlightened’ One. The Buddha was born as Siddhartha Gautama in Nepal around 2,500 years ago. Siddhartha was born into the royal family of a small kingdom on the Indian Nepalese border. He is believed by Buddhists to be a human being who became Enlightened (awakened).

Dharma: universal law; ultimate truth. The teaching of the Buddha.

The Jataka Tales or Birth Stories form one of the sacred books of the Buddhists and relate to the adventures of the Buddha in his former existences, in both human and animal form. The Buddha was a great storyteller and often told stories illustrate his thinking. Stories were also told about the Buddha by his followers both to explain and understand the Dharma. These stories have been passed down to the present day and the most popular ones are the Jataka tales, a collection of hundreds of tales about the Buddha’s past lives. They show the kind of life one should lead to become a Buddha one day. In many of these stories, the Buddha appears as an animal to teach the value of qualities such as kindness, compassion, and giving.

Karuna: compassion. The importance of being compassionate, generous, kind, truthful, helpful and patient: Actions have consequences.

Learning activities

Resources:

This lesson requires several images and a video clip of Siddhartha’s life. You will need to find these online before you start.

Images: lotus flower, Prince Siddhartha, Gautama Buddha

Video clip: the life of Siddhartha Gautama, or the life of the Buddha

Show the class an image of a lotus flower. This is a well-used symbol in both Hinduism and Buddhism and you will find may examples online.

Explain to the children that the flower is a lotus flower and that this is a symbol that is frequently used in Buddhism, because it shows how something beautiful and precious can grow out of the soil of the earth. Explain that they will be thinking about the most valuable things in the world in the next few sessions and that this will include an investigation into what followers of the Buddha – Buddhists – think is most valuable.

Ask the children for their ideas about what is most valuable (a) in their lives and (b) in the world.

Explain that in Buddhist philosophy many people can be seen as too distracted to see what is really valuable in life. The person whose teachings they follow became known as ‘The Buddha’ and they are going to find out about his life and what he taught.

Write the names ‘Prince Siddhartha’ and ‘The Buddha’ on the board. Play the video clip you have found. Explain that at the end you will talk about how the Prince became The Buddha. Play the video.

At the end of the film, show the children a picture or image of the Buddha and ask them to recall the story: what do they think were the most important parts? Record what pupils say on sticky notes and share with class, placing answers around the image.

Ask the children to share experiences and feelings about times when they have done something that was extremely difficult, for example, learning something new or embarking on something that will take a long time. What do they think were the difficult things that Prince Siddhartha did when he went on his search for the truth about life? Ask them to complete the sentence, “I think the hard challenges that Prince Siddhartha had to face were…” and to explain why they think these were hard challenges. Can they think about how he might have been feeling when he saw the old man, the sick man, the dead man and the ‘seeker’? [This activity could be done as a ‘hot seat’ activity for lower KS2].

Ask the children to share experiences of times when members of the class have experienced or done something that put the needs of others before their own. Ask them to respond to such questions as:

- Have you ever given away something you wanted for yourself?

- What did you give away?

- Was it easy to do?

- Why did you do it

- How did you feel?

- What effect did it have on you / the other person?

- Encourage them then to complete a couple of sentences such as:

- I put others first by ………………………………………………………………

- This made me feel ………………………………………………………………

Some children could go on to draw a picture of an experience of a time when they put others first, and write simple sentences about it.

Next, remind the children of the part in the film where the Buddha remembers all his ‘past lives’ and explain that Buddhists believe that when a person dies they will usually be ‘reborn’ in a different form depending on how they have lived their life. There are many stories in Buddhism that describe the Buddha’s previous ‘lives’, sometimes as an animal. These stories show how the Buddha did many helpful things in his previous lives and this helped his progress from one life to the next. One of these stories is about a monkey king who put others before himself.

Download the story: http://www.clear-vision.org/Fileshttps://clearvision.education/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/MonkeyKing.pdf/MonkeyKing.pdf

Read the story from the beginning and stop at the point where a mango falls into the water and drifts downstream. Ask the children to talk with each other about what might happen next.

Read the rest of the story. Stop reading from time to time to check understanding.

Engage the children in a sequencing activity to help them recollect the main aspects of the story. Provide them with a set of the following sentences on separate cards [You could also provide the pupils with a set of six picture cards depicting these scenes: you can find these in the Clear Vision pack if you have it]:

- A little monkey found a mango.

- “Pick those mangoes”, said the Monkey King.

- The King found the mango.

- The King saw the monkey’s tail.

- The Monkey King held on.

- The Monkey King died.

Ask the children to work in small groups to put the cards in sequence, making sure they can justify their choice of order. Most children can then go on to write their own sentence for each picture, using some key words that you can put up on the board: Moon, mountain, river, monkey, mango, tail, King, died, tree, bridge, monument. Some children may be able to independently write up the story, using illustrations and key words as support.

Next, engage the children in a drama re-enactment of the story. [This could also be adapted for a Music activity, with children choosing choose a variety of musical instruments which will they think will express the emotional tempo of key events in the story, e.g., finger cymbals – calmness, drums – the King’s men approaching, bells to build up to tension, or an Art activity with children using different media to make props representing, e.g., masks, river, tree branches, crowns.]

Ask them to imagine that they are one of the band of monkeys living harmoniously in the mango tree. Take them through the following actions:

- Climb the tree.

- Explore.

- Eat and enjoy the mangoes.

- Sleep, play and carefully pick all the fruit that hangs out over the water.

- Tell them that the human King and his soldiers arrive: hide in the bramches.

- You are very frightened. Try not to move or make a sound.

- You see the monkey King leap over the river and make himself into a bridge. [Use long piece of ribbon or string and lay it on the floor to represent the bridge.]

- One at a time, quietly and carefully, cross the bridge to safety.

Then ask the children to respond to such questions as:

- How did it feel living in the tree?

- How did you feel hiding from the King?

- Why did you cross?

- What advice would you give to those who have yet to cross?

- How did you feel when the monkey king made himself into a bridge for you to cross?

- How did you feel when you escaped?

- When did you feel safe?

- What would have been the consequences if you didn’t cross?

- How would the world change if everyone was selfish?

- Who would you look to in your life to guide you in times of fear?

- Why might Buddhists think this story is a good one?

Prepare the outline of a mind-map on what the Monkey King might be thinking and show it to the pupils. Ask them to complete their own version in small groups and to share their ideas with the rest of the class.

Encourage the children to then offer views about what Buddhists might believe this story tells them about what is of great value and to add their ideas on the edge of their mind- map diagrams.

Engage the pupils in a ‘Conscience corridor’ activity around the Monkey King’s sacrifice:

- Select one pupil to be the Monkey King and ask the rest of the class to create two lines approximately a meter apart facing each other.

- Ask pupils on one side of the ‘corridor’ to think or a reason for the Monkey King to act selfishly and just save himself. Ask pupils on the other side to take the opposite view and think of a reason for the Monkey King to sacrifice himself to save the other [Pupils could choose which viewpoint they wish to voice or be told which view point to take.]

- The Monkey King then walks slowly through the corridor and pupils on each side whisper their reasons. [Pupils who lack confidence can ‘pass’ by clapping or repeat a comment that has already been spoken.]

- Once the King has reached the end of the corridor, ask them to recall the main reasons on either side and to say what they would have done in the King’s What were the main reasons for their decision?

- Ask the other children to say what they think they would have done, with reasons that link the situation to their own lives and experiences.

The ‘Conscience corridor’ activity could then be repeated, but with a different pupil playing the part of the human King. This time the dilemma is whether to order his men to shoot the Monkey King:

Again, at the end of the corridor, ask the pupil playing the part of the human King to recall the main reasons given on either side and to say what they would have done in the King’s situation. What were the main reasons for their decision? What do they think a Buddhist would do, and why?

At the end of the activity, engage pupils in a class discussion and write up their ideas on sticky notes to put on a ‘Monkey King’ poster. Ask them for their responses to such questions as:

- What is the opposite of selflessness?

- What does the story tell us about greed?

- What is ‘compassion’?

- How did the Monkey King show compassion for others?

- What is ‘sacrifice’?

- What sacrifice did the Monkey King make?

- Who do you know that is selfless in your life?

- What does it mean ‘to set a good example’?

- In what ways did both kings in the story set a good example?

- Can you think of how people could set a good example, in the school, or locally or globally?

- What is ‘wisdom’?

- What does the story tell us about the qualities of a good leader?

- What do you think happened to the human king after the monkey king died? Did he change his life? Did he grow in wisdom?

- Finally, encourage pupils to add their own sticky note to the poster, completing this sentence:

I think that Buddhists value ………… the most.