Origins

The Shema may be seen as the beginning and end of Judaism. It is a Jewish prayer extracted from three places from the Torah and composed into a sequence of paragraphs. It does not appear in its entirety at the beginning of the Torah, rather it is found in Deuteronomy 6.4-9; 11.13-21 and Numbers 15.37-41. The Shema derives its name from the Hebrew word sema, meaning ‘to hear’, which is the initial word of the first verse, which states, ‘Hear O Israel’. Thereby, instructing Jews to listen. It is believed that they were received by Moses on Mount Sinai.

Significance

The Shema is included as part of every weekday synagogue service. Its significance is inferred by the fact that its centrality is recognised in all Jewish traditions, in various ways. The recitation of the passage is taken as a commandment to be fulfilled by Jewish adult men twice daily, morning and evening. It is also a core text in other prayer books.

The Shema is taught for the love of God, loyalty to the Jewish tradition and it encourages the Jewish community to study the Torah. It is reported that Jacob’s sons read it to him and therefore adults recite it to children so that they remain within their tradition. The Shema might be the first thing that some Jewish children learn in a Jewish primary schools and at home to express belonging.

Meaning

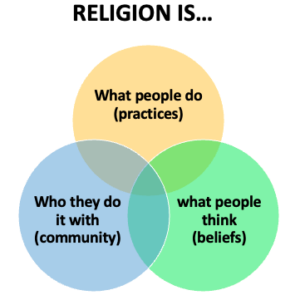

The Shema sets out what Jews believe and how they should demonstrate their dedication to God through daily actions.

It represents their belief that they have made a Covenant with God: an agreement that they will love God and follow His laws and in return God will take care of them. Thus, as an artefact, the Shema is a way for Jewish people to remind themselves of their promises to God. This is why families have a responsibility to teach their faith to the next generation.

Practice

Unsurprisingly, the Shema has acquired a pivotal position in the collective and personal life of Jewish communities. Communally, adults recite it in the morning and evening and in the afternoon at the synagogue to fulfil the commandment and remember God.

Individually, some Jews recite it before bed and after waking up, as it is the most holy thing to say during these times. It is also a way of thanking God for waking them up from sleep and to ask God for good sleep. Thus, it is a prayer which covers all activities of the day and night.

As a family, in some homes, mothers regularly recite the Shema with their children whilst putting them to bed. Some children memorise it and others prefer to look at the text when reciting it.

At happy events, such as moving into a new home, the mezuzah, which contains the Shema, is fixed to the doorpost and is followed by a religious service.

During festival days and especially on Shabbat, a double reading honours the Shema: at the time the Torah scroll is bought out from the Ark the opening verse of the Shema is recited collectively, and again, individually by the reader prior to reading the Torah.

There are some physical gestures adopted by Jews during various prayers and worship. On the Day of Atonement whilst reciting the opening verse of the Shema, the eyes are covered to remove distractions.

As death approaches, those gathered recite some passages from the Torah and end with the opening words of the Shema. In this way the dying person is helped to affirm their faith in the oneness of God. It is worth noting that the Shema may be recited in Hebrew and in other languages too.

Structure

The Shema has three paragraphs. The English translation is provided with an explanation of what it might mean to some Jews, how they might put it into practice and what they could learn from it.

Hear O Israel, the Lord is our God, the Lord is One (Deuteronomy, 6.4)

From this, Jews learn to be attentive to the Torah so that God’s commands are with them. It also means their religion is monotheistic. Moreover, a closer examination reveals God as addressing Israel rather than Israel addressing God, thus Jews make claims of a reciprocal relationship because God chose them, and consequently, they believe God cannot ignore them.

Blessed is His name, whose glorious kingdom is forever and ever

This phrase does not appear in the Torah and is attributed to Jacob. Since he had whispered it, Jews whisper it as well. It tells the Jewish community to praise God. They know, through this, that God’s kingdom is everlasting. They recognise the holiness and greatness of God. It gives them hope too.

Love the Lord your God with all your heart, and all your soul, and all your might (Deuteronomy, 6.5)

The demand from God is unequivocal in this phrase: total obedience and wholehearted devotion and to remember God’s word. It implies that Jews be prepared to sacrifice everything. They are to love God with their might, heart and soul. God loves them; therefore, they too should have unflinching love for Him.

These words that I command you today shall be upon your heart (Deuteronomy, 6.6)

Jews learn to affirm these as laws and learn them orally. But there is also an emotional attachment. The heart is mentioned so that it can act as a guide following the dictum ‘in doing right follow your heart’, and in the heart should be the Torah.

Repeat them to your children, and talk about them when you sit in your home, and when you walk in the street; when you lie down, and when you rise up (Deuteronomy, 6.7)

This phrase gives adults the responsibility to pass on their faith to children, and this can take place in formal and informal settings. The key message is to keep it alive at all times. Literally, it means Jews should recite it every evening and morning.

Hold fast to them as a sign upon your hand, and let them be as reminders before your eyes (Deuteronomy, 6.8)

Literally, this means to hold fast onto the Shema and the Torah by wearing the verses on the hand and upon the forehead between the eyes. This is how the practice of wearing phylacteries (tefillin) became established. The tefillin consists of four small joined-up boxes containing the first two passages of the Shema (Deuteronomy, 6.4-9 and Deuteronomy, 11.13-21) and two other Exodus phrases of the Torah. These are handwritten on a parchment and worn on the stronger hand as this is what is used by individuals or on the left arm so that it is directed to the heart. It is a constant visual reminder for Jews that God is there, whatever they do.

Write them on the doorposts of your home and at your gates (Deuteronomy, 6.9)

The final instruction is to handwrite a parchment and fix it to the doorpost of the home and gates. In practice, to preserve the sanctity of the text, a rectangular elongated box with a slight opening, called a mezuzah, is made to house this kosher parchment, which contains the first two of the three paragraphs of the Shema (Deuteronomy, 6.4-9 and Deuteronomy, 11.13-21) and at the back, the word Shaddai (Almighty). The mezuzah is affixed on the right hand doorframe, with a little slant upwards in the direction of the room, at about shoulder height, in individual dwellings and collective compounds. In doing so, most Jews express their obedience, and, when they come into and go out of their homes, they are reminded to renew their covenant daily. The mezuzah is fixed on every door (except the lavatory and bathroom), so the whole house is covered in holiness and purity as a gift of God. Some Jews kiss the mezuzah to show their adherence to the Torah in everything they do, including daily actions like entering and leaving the home.

Mezuzah literally means ‘doorpost’, but over time came to refer to the doorpost and what is attached to it. Interestingly, a sukkah does not need a mezuzah as it is not permanent dwelling.

Deuteronomy 11.13-21

This section is an exhortation to obey, love and serve God alone with everything. In return God promises the Jewish community abundance in material well-being. Should they turn to serve other gods, the anger of God awaits them (Deuteronomy, 11. 13-17).

The next phrases (Deut. 11.18-21) repeat the instructions given above in (Deut. 6-9). Thereafter, God promises that should these be fulfilled then God will keep His promise of the land for them (Deut. 11. 21).

Numbers 15.37-41

This verse establishes the custom of Jews adorning clothes with tzitzit (fringes). Tzitzit are tassels made of several threads tied together to symbolise the numerical value of the name of God. The Shema says that when people look at the tassels they will remember their promise to keep God’s laws. Some Jews follow this rule all the time and wear a vest with tassels on four corners, called a tallit katan. At the synagogue, some also wear a special prayer shawl called a tallit gadol when praying in the morning.

To summarise, the Shema is a prayer in the first instance and a belief statement thereafter. It has a golden principle for the Jewish community in stressing that learning is initiated at home and establishes the duty to educate their children in the faith. The Shema establishes the practice of learning the three paragraphs contained within it, and of wearing the tefillin and affixing the mezuzah. These actions remind Jewish people of the promises made to and by God, their belief about unity of God and the One to be worshipped.

Learning about the Shema in RE

Here are some examples of what primary pupils might be able to do as a result of their learning about the Shema.

They can:

-use the right names for things that are special to Jews, e.g. when shown a picture, say: ‘That is a mezuzah’

-talk about what they find interesting or puzzling, e.g. talk about how interesting it was to hear that Jewish people put a prayer in a small box and fix it to their doorposts

-talk about some things that are similar for different religious people, e.g. say that Muslims, Christians and Jews all says prayers to God

-talk about some things in stories that make people ask questions, e.g. say, ‘It was mysterious when God spoke to Moses’

-describe things that are similar and different for religious people, e.g. record or say how Jews recite the Shema, but that they may say it in different languages

-ask important questions about life and compare their ideas with those of other people, e.g. ask why Jews think the Shemais such an important prayer and give their own ideas about important prayers and wishes

-use the right religious words to describe and compare what practices and experiences may be involved in belonging to different religious groups, e.g., say how different Jewish communities might have different ways of remembering God’s laws – through recitation of the Shema, through wearing of the tallit and tefillin, though doing good deeds and so on

-ask questions about the meaning and purpose of life, and suggest a range of answers which might be given by them as well as members of different religious groups or individuals, e.g. asking questions about the importance of the Shema in Jewish life and suggesting answers that might be given by a Jewish visitor to the classroom, or with reference to answers given in authoritative texts or websites.

Some common discussion questions:

- What do you think it means when the Shema says: “These words […] shall be upon your heart”?

- In the Shema, where does it say that Jews should talk about God’s laws?

- Why do you think the Shema says that Jewish people should repeat the words to their children?

- What could you use or do to help you to remember promises that you have made?

Further reading

Cohn-Sherbok, D. (2003) Judaism: History, Belief and Practice, London: Routledge.

Hoffman, C. M. (2010) Judaism: An Introduction, London: Hodder Education.

Written by Imran Mogra