An investigation into differering Christian repsonses to environmental issues.

for 15-19 year olds. Originally written by Anna Davis, updated in April 2019.

Key words and concepts

Anthropocentric: human-centered; focusing on human beings as of most value and importance, especially in relation to animals or the rest of the natural world.

Apocalyptic: in biblical studies, refers to a kind of literature that reveals God’s perspective on current and future events, often with vivid and coded imagery, stark opposition between good and evil, and a prediction of what is to come. The best-known biblical example is the Book of Revelation (the Greek title of which is equivalent to the word ‘apocalypse’) in the Bible

Conservative Evangelicalism: a Christian tradition, found across a range of established and independent churches, which places particular emphasis on the authority and infallibility of the Bible, among other doctrines.

Dominion: sovereignty or control. Especially used to refer to the idea that humanity has power over the rest of creation. See Genesis 26-28.

Ecology: the part of biology that looks at how different organisms relate to one another and to their physical surroundings. Some environmentalists are concerned that human activity is damaging the delicate balance of ecology and thus endangering the future of the planet.

Ecosystem: a particular group of organisms that understood in relation to their physical surroundings.

Environment: the natural world, particularly as it is affected by human activity.

Environmentalism: a movement that is concerned with protecting the natural world from the harmful actions of humanity.

Eschatology: used by theologians to refer to beliefs about the future, and particularly about the ultimate ‘end’ of the world. It comes from the Greek word ‘eschatos’ meaning last or final. Also used to talk about God’s plans for the future of creation, including humans, animals and the environment.

Evangelism: spreading the Christian gospel with the particular aim of converting people to Christianity.

Francis of Assisi: an Italian Catholic friar and preacher of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries who founded a number of monastic orders and has become known as the Patron Saint of animals and the environment.

Fundamentalism: in this context, a form of Christianity focused on what are believed to be its fundamentals, with a particular emphasis on the authority, infallibility and inerrancy of the Bible. This label overlaps with Conservative Evangelicalism (see above).

Gaia hypothesis: the view of scientist James Lovelock that the earth is a kind of superorganism – a complex system that automatically self-regulates in ways that maintain an environment in which life can flourish.

Genesis: The first book of the ‘Old Testament’ or ‘Hebrew Bible’. It begins with two accounts of God’s creation of the world and contains various commands by God about how humans should act in relation to other parts of creation. These commands have been the subject of differing interpretations, hence the existence of current debates about how Christianity should respond to environmental challenges.

Global warming: a gradual increase in the temperature of the earth’s atmosphere and oceans. Generally attributed to the ‘greenhouse effect’, which is caused by increased levels of carbon dioxide, CFCs and other pollutants as a result of human activity. There is concern that global warming could cause sea levels to rise, having catastrophic effects of human life.

Imminent expectation: in this context, refers to the belief of some Christians that Jesus will return soon – perhaps within their lifetimes – to bring about the final end of the world.

Parable: a story or image used to illustrate a moral or spiritual lesson, as told by Jesus and recorded in the Gospels.

Rapture: the transporting of believers to heaven during the Second Coming of Jesus at the end of the world.

Stewardship: in Christianity, the idea that humans have been given responsibility for the rest of the natural world, and have a duty to care for it.

As well as enabling students to engage critically with different approaches to environmental stewardship, this material also develops knowledge about the Bible, and the different ways this can be approached and understood. Different methods used in Biblical Studies underpin this, as outlined below:

Historical criticism

Historical criticism is based on the presumption that the task of the biblical scholar is to discern what the text originally meant, and what events actually happened, from an objective and unbiased perspective. It has value not least in ‘distancing’ the Bible from its contemporary readers: the Bible is a collection of ancient texts, rooted in the cultural assumptions of ancient societies, that cannot cogently be regarded as simply a textbook of eternal religious or moral truths. Using this method, students can be encouraged to approach biblical texts critically, as historical sources. They may, for example, seek to identify different sources and traditions, to question which sayings of Jesus are likely to be authentic, or to consider aspects of biblical teaching that reflect ancient cultural or cosmological presuppositions. Historical criticism is no longer an uncontested or dominant method in biblical studies since it has been recognised that detached, objective historiography is impossible, and may in fact serve to conceal the interests and commitments that underlie particular construals of the past and particular readings of the texts. Nonetheless, it remains significant to a critical engagement with biblical texts as part of the study of topics such as environmental ethics.

History of interpretation

A recent development of interest within biblical studies is in the history of interpretation and influence of biblical texts (their Wirkungsgeschichte). Rather than looking to the world behind the text – the social context in which it arose, as in historical criticism – this approach instead concentrates on the world in front of the text, that is, on the diverse ways in which the text has been understood and has shaped and influenced aspects of life and culture from art and music to ethics and politics. This method means that rather than assuming that the text has one clear, correct meaning, and attempting to decide upon this, attention is directed instead to the diversity of meanings that has, through history, been derived from this text. In relation to environmental issues, it enables consideration of how Christians at different times and places have interpreted texts like Genesis 1–2 in relation to their particular convictions and concerns. It also serves to connect biblical studies much more directly with the study of issues and approaches in Christian ethics, from the earliest times right up to the present.

Reading from modern perspectives: the located reader

More recent methods of biblical study reflect the conviction that different readings can be generated depending on the social identity and location of the reader, and have given rise to feminist, black, liberationist and many other readings of the Bible. Such approaches place much greater emphasis on the role of the reader in the construction of meaning and on the influence of the reader’s context – a development which is also to be found in the study of other kinds of literature, as well as in disciplines such as history and politics, given a widespread acknowledgment that objective and detached analysis is impossible, and that the researcher’s own convictions and approach shape their presentation. Students might therefore be encouraged to ask how modern convictions and contexts shape readings of the Bible, or how different groups might read and respond to different texts.

Christian perspectives on the environment

The Evangelical Churches and Organisations

There are a number of evangelical Christian organisations that strongly support the idea that Christians must care for the environment. Stewardship is a prominent theme.

The Evangelical Environmental Network has stated that:

Because we have sinned, we have failed in our stewardship of creation. Therefore we repent of the way we have polluted, distorted, or destroyed so much of the Creator’s work.

They argue that we need to take better care of creation – to become better stewards – in order to live as God desires. (On the Care of Creation)

Other motivations for environmental care include an appeal to love of neighbour, encouraging people to act justly and out of consideration for those who are less fortunate. For example, the Evangelical Environmental Network includes ‘human and cultural degradation’ as among the ways in which we harm creation when we fail to act as stewards.

Tearfund, the Evangelical Alliance’s relief fund, campaigns on a variety of global humanitarian concerns including matters affecting the environment and climate change to encourage people to consider how their actions harm those who live in countries that are adversely affected by climate change. It cites a paraphrase of Romans 10.13 – ‘Love does no harm to its neighbour’ – as a call to responsible stewardship so that others do not suffer from the effects of climate change.

The Church of England

In 1991, the General Synod of the Church of England prepared a report on ‘Christian Stewardship’ with the aim of encouraging ‘a critical review of human responsibility to the living environment’. It states that:

Christians believe that this world belongs to God by creation, redemption and sustenance, and that he has entrusted it to humankind made in his image and responsible to him; we are in the position of stewards, tenants, curators, trustees or guardians, whether or not we acknowledge this responsibility.

The report cites Genesis 1.26-30 as giving humans authority over the natural world. However, at the same time it reads Genesis 2.15-17 as instructing humans to both ‘work’ it and ‘care’ for it. So humans have ‘dominion’ over the earth but this is a gift from God. This means that humans should care for the world ‘in the way God himself demands’.

Other motivations for environmental care include an appeal to love of neighbour, encouraging people to act justly and out of consideration for those who are less fortunate. For example, the Church of England writes of how ‘we are tenants of the world only in our own generation’, highlighting the importance of preserving the natural environment out of concern for the wellbeing of future generations. (Christians and the Environment: Report by the Board for Social Responsibility).

The Catholic Church

The Catholic Church understands stewardship as resulting from humans having been created in the image of God (the Catholic doctrine of the imago Dei).

Agneta Sutton from the Catholic Truth Society writes that:

From the very first, the biblical account of our role in creation declares that we have a special position and stand in a special relationship to God and so to the rest of creation. (Ecology and Stewardship: What Catholics Believe About the Environment. London: CTS. 2012. p. 8)

The International Theological Commission states that humans are:

…made in [God’s] image to participate in his work, in his project of love and salvation, indeed in his own lordship over the universe. Since man’s place as ruler is in fact a participation in the divine governance of creation, we speak of it here as a form of stewardship. (Communion and Stewardship: Human Persons Created in the Image of God, Section 57)

Pope John Paul II, a former leader of the Catholic Church, has spoken of the need for an ‘ecological conversion’. He remarks that:

Man’s lordship is not absolute, but ministerial…not the mission of an absolute and unquestionable master, but of a steward of God’s kingdom. (Communion and Stewardship, Section 73)

So for Catholics, ‘God appoints man as his steward in the manner of the master in the Gospel parables (cf. Luke 19:12)’. (Communion and Stewardship, Section 58).

The Orthodox Church

The Orthodox Church understands Genesis 1 as a call to stewardship, requiring humans to be responsible for creation. This is also linked with the Orthodox emphasis on ‘deification’ – the idea that humans come to share fully in God’s being and nature through the process of salvation. The Report of the WCC Inter-Orthodox Consultation states that:

We are called to exercise dominion over all creatures on earth (cf. Gen. 1:28), i.e. to be stewards … of God’s material world, caring for it, maintaining it in its integrity and perfecting it by opening it up to God through our own deification. (Orthodox Perspectives on Creation, Section 11).

Orthodox theology also places emphasis on the importance of priesthood, not only as an office within the Church, but as a role that can be played by humanity in relation to the rest of creation: humans can help to offer the creation to God and mediate and express its praise to God. This may be linked with the idea of ‘deification’: the goal for humanity and for creation is to be transformed, renewed, perfected, and taken up into God. Some have suggested that these ideas about the transformation of all creation – its incorporation into the divine – may be especially valuable ideas to inspire environmental care. They express different ideas and emphases from the kind of stewardship expressed in the Protestant Churches, which is more concerned with the role of humans in relation to the rest of creation.

Conservative Evangelical and Fundamentalist Christian groups opposed to environmentalism

Not all Christians agree that we should be concerned about preserving the environment, or acting to reduce carbon emissions. Some conservative evangelical and fundamentalist groups see the environmental movement as a dangerous threat – a false, non-Christian religion.

It is important to note that such groups do not necessarily reject the idea of stewardship, but that they understand it in particular ways. Members of such groups are likely to put greater stress on the importance of evangelism (converting individuals to faith), the imminent return of Jesus, and ethical values related to sexual and family ethics than on conservation or care for the planet. Certain biblical texts to do with the end of the world are of particular importance here, for example, 1 Thessalonians 4.13-5.2 and Mark 13.7-31.

Sometimes these views are expressed in academic books, or on organisations’ websites, but more often they are to be found at a popular level on individuals’ blogs and websites.

For example, the American Evangelical organization Cornwall Alliance for the Stewardship of Creation the environmentalist view of the world which it claims ‘elevates nature above the needs of people, of even the poorest and the most helpless’. The Cornwall Alliance argues that such environmentalism is a ‘green dragon’ that presents a major threat to the Christian religion.

Further, Calvin Beisner, spokesman for the Cornwall Alliance, sees the domination of nature by humans as an essential task. He writes: ‘…continued population growth will result not in the depletion but in the increased abundance of resources, and not in increased pollution of the earth but in its increased cleansing and transformation from wilderness to garden, “from its bondage to decay…into the glorious freedom of the children of God” (Rom. 8:21).’ (Where Garden Meets Wilderness: Evangelical Entry into the Environmental Debate. Grand Rapids, MI: Acton Institute for the Study of Religion and Liberty/Eerdmans. 1997. p. 107)

In more popular literature, Spencer Strickland, through a blog published by Jeremiah Daniel McCarver, ‘Saving Earth One Human at a Time’ draws attention to the impact of beliefs about the imminent end of the world on concern for the environment:

Christians should not be carried away into the frenzy that is being stirred up in popular culture. While it is true that we are all stewards of the earth and should thus take care of it, we should also be aware of the fact that the “heavens and earth which are now” are being prevented from being destroyed by the Word of God (2 Pet. 3:7). God will one day destroy the earth with the fire of judgment, and this is the warning that Christians must take to those who are lost, in order that they might be saved through the obedience of the Gospel.

Similarly, Todd Strandberg, writing on his website ‘Rapture Ready’ states that, in his view, ‘any preacher who decides to get involved in environmental issues is like a heart surgeon who suddenly leaves an operation to fix a clogged toilet.’

Learning activities

1 Is Christianity to blame?

As a class, read and discuss the ‘Beyond Stewardship?’ stimulus text ‘Lynn White: Is Christianity to blame for our ecological crisis?’ Available to download here.

2 Origins of stewardship

Divide the class into small groups. Give each group one of the following texts:

Genesis 1

Genesis 2

Genesis 3

Genesis 4

Within their groups, the students read the texts and then discuss whether:

- the text encourages care of the planet?

- the text suggests humans are ‘in charge’?

- the text suggests the land has intrinsic/instrumental value?

- humans being made in the image of God change their relationship with the Earth?

The students should be encouraged to give reasons for their answers, and should refer to the texts the back up their views.

The groups can present their findings and views about the text they have studied to the rest of the class.

3 Contemporary Christian views

Display images depicting modern environmental problems, such as the destruction of the rainforest to grow palm oil, collapse of insect populations, reduction in water tables for cotton production and plastic pollution. Discuss what the images suggest about contemporary attitudes towards how we should care for the environment. Can any implications be drawn about Christian attitudes?

Establish the critical question: Is Christianity to blame for the Ecological Crisis? This is based on Lynn white Jr’s argument.

Divide the class into small groups. Give each group:

- one of the viewpoints from the ‘Christian Perspective’ section of this resource;

- a large recording sheet with space for notes on their Christian viewpoint, and THREE additional viewpoints.

Using their recording sheet, each group works together to create succinct notes recording their viewpoint and three others in relation to the critical question.

After reading and discussing their viewpoint, groups send one or two envoys to other groups to discuss and learn about other viewpoints, before returning to their original group.

Allow plenty of time for reading, discussion, definition and note-taking. Students will end up with a multi-layered analysis of Christian views and a critical view.

If time, listen to a brief answer from each group to the critical question, or set as a written homework, drawing on the evidence gathered.

4 How do different Christian views shape the argument?

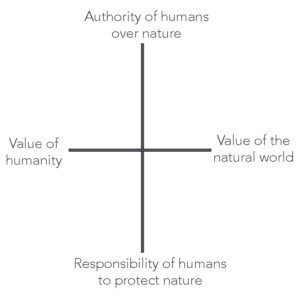

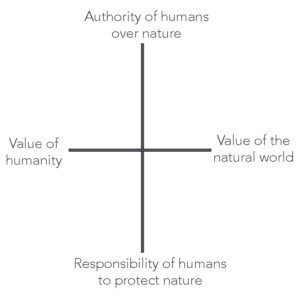

Ask groups to copy this graph:

In groups, place each Christian perspective on this graph: do they place human authority over nature above human responsibility to protect nature; do they value humans above the natural world, etc?

Share and discuss graphs. As a class, ascribe reasons to each positioning; what are they based on? Either give a theological argument or a biblical reference to support each position. Through the course of the conversation, ensure these two positions are defined:

Christian Environmentalism: humans must transform the way we treat the environment; the natural world must be protected and nurtured, in both Evangelical and denominational Christian thinking.

Conservative Evangelical or Fundamentalist non-Environmentalism: God will destroy the earth at the End Times, this is God’s plan for humanity and the natural world.

Debate

Divide the class into two groups: Christian Environmentalism and non-environmentalism. Each groups has 15 minutes to create 4 strong arguments in favour of their position, in response to the motion (below).

Groups should also predict counter-arguments and prepare to meet them.

Motion: The earth is ours to use